Rwanda has made impressive gains 30 years after a devastating genocide. But ethnic divisions persist under President Paul Kagame, whose harsh methods carried the transformation.

But ethnic divisions persist under an iron-fisted president who has ruled for just as long and Under Rwanda's Constitution, he could rule for another decade.

The milepost has given new ammunition to critics who say that Mr. Kagame's repressive tactics, previously seen as necessary.Blood coursed through the streets of Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, in April 1994 as machete-wielding militiamen began a campaign of genocide that killed as many as 800,000 people, one of the great horrors of the late 20th century.

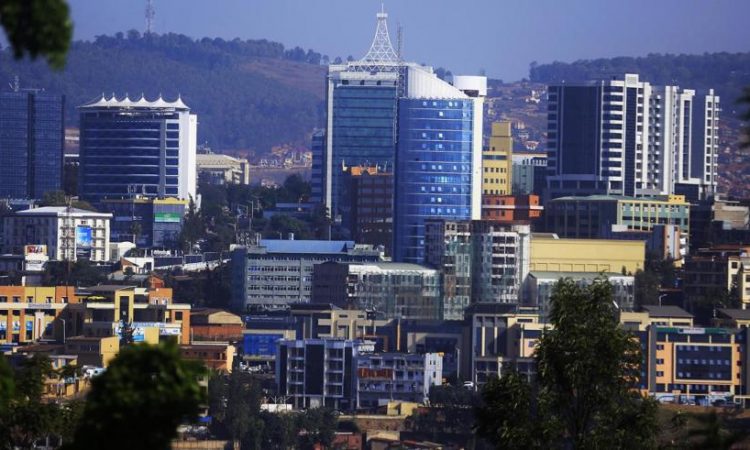

Thirty years later, Kigali is the envy of Africa. Smooth streets curl past gleaming towers that hold banks, luxury hotels and tech startups. There is a Volkswagen car plant and an mRNA Vaccine Facility. A 10,000-seat arena hosts Africa’s biggest basketball league and concerts by stars like Kendrick Lamar, the American rapper, who performed there in December.

Tourists fly in to visit Rwanda’s famed gorillas. Government officials from other African countries arrive for lessons in good governance. The electricity is reliable. Traffic cops do not solicit bribes. Violence is rare.

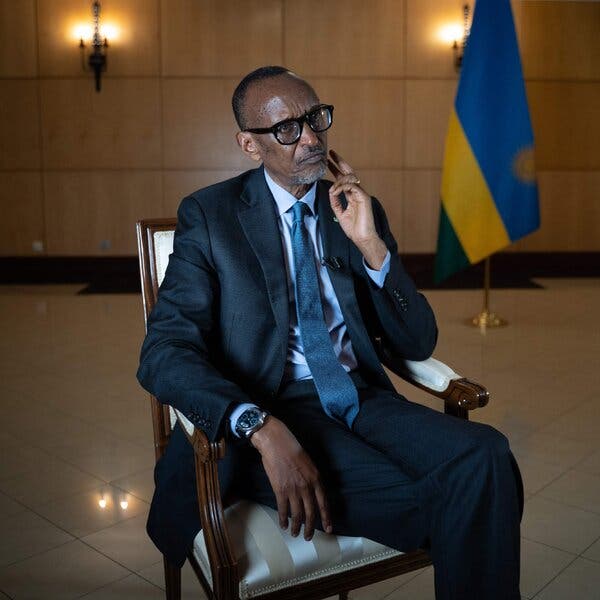

The architect of this stunning transformation, President Paul Kagame, achieved it with harsh methods that would normally attract international condemnation. Opponents are jailed, free speech is curtailed and critics often die in murky circumstances, even those living in the West. Mr. Kagame’s soldiers have been accused of massacre and plunder in the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo.

The United Statesvand and the United Nations have publicly accused Rwanda of sending troops and missiles in support of M23, a notorious rebel group that swept across the territory in recent months, causing widespread displacement and suffering. The M23 has long been seen as a Rwandan proxy force in Congo, where Mr. Kagame’s troops have been accused of plundering rare minerals and massacring civilians. Rwanda denies the charges.

The crisis has cooled Mr. Kagame’s relations with the United States, his largest foreign donor, American officials say. Senior President Biden administration officials traveled to Rwanda, Congo and, more discreetly, Tanzania in recent months in an effort to prevent the crisis from spiraling into a regional war. In August, the United States imposed sanctions on a senior Rwandan military commander for his role in backing the M23.

U.S. officials described tense, sometimes confrontational meetings between Mr. Kagame and senior American officials, including the U.S.A.I.D. administrator, Samantha Power, over Rwanda’s role in eastern Congo.

Mr. Kagame has often denied that Rwandan troops are in Congo, but he appeared to tacitly admit the opposite in a recent interview with jeune Afrique Magazine.

In justifying their presence, he fell back on familiar logic: that he was acting to prevent a second genocide, this time against the ethnic Tutsi population in eastern Congo.

Thankyou for the Scheduled Quality Ample Time.